This is not a real orrery (mechanical model of the Solar System), it just plays one on TV. Lots of things look pretty reasonable if you don’t think too deeply about them.

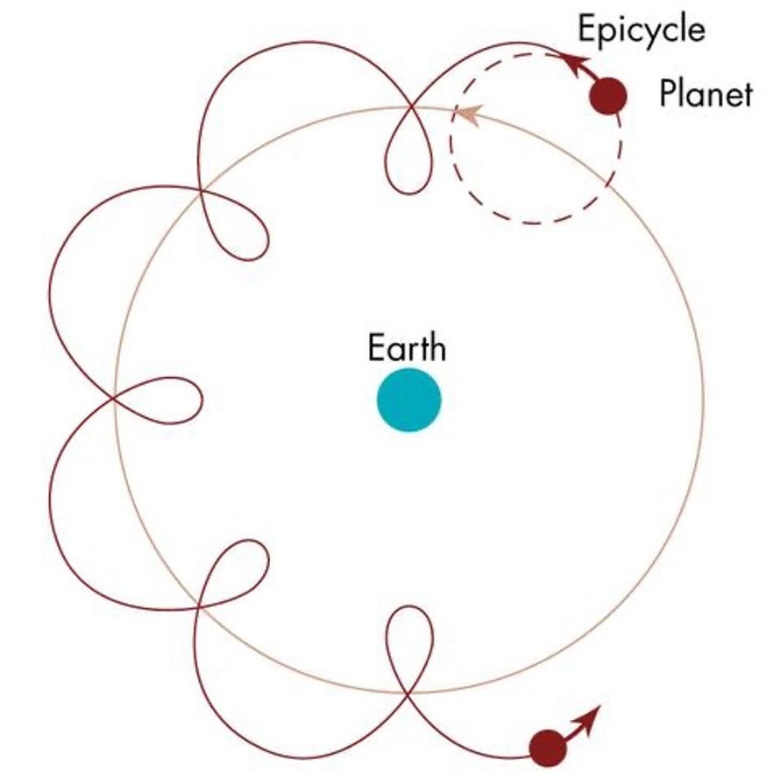

For two thousand years, the relative motions of the Moon, Sun, and the (at the time, five known) planets were described using a conceptual model based on a geocentric (Earth-centered) view of the system. Each planet was assumed to move around the Earth in a perfectly circular orbit (circles being an ideal geometric shape). As it became clear that circular orbits were not consistent with the paths of motion of celestial objects, the model was updated by proposing “epicycles” -- circular trajectories whose centers were on the original circular orbits. As is obvious, no epicycles are required in the modern understanding of the Solar System, with elliptical orbits centered around the Sun, not the Earth.

The story of adding complexity in order to account for additional data that does not fit the model is considered apocryphal, but the idea of “adding epicycles” to rescue a troubled hypothesis remains an important cautionary metaphor about special pleading in science to this day. In fact, the use of linguistic epicycles is commonplace among science deniers everywhere, from Young Earth Creationists to Moon Landing Hoaxers. Adding epicycles is a sure-fire way to ensure that your theory doesn’t hold up to Occam's razor.

If you’ve been following the news during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, you may have noticed that public health messaging has had a strongly epicyclic quality to it. The meanings of (previously well understood) words such as “airborne”, “endemic”, “variant” and “immunity” have morphed, sometimes more than once, in service of public health narratives around COVID-19 and its impacts. These epicycles have served to grease public health guidelines (and historical narratives about the pandemic) with a certain linguistic slipperiness.

Talking in circles

First, let’s dive a bit deeper into the ways in which experts and public health have talked themselves in circles during this pandemic, shall we? Here are some ways in which linguistic confusion has been exploited during the current pandemic, to the detriment of the public’s health.

Airborne

Before the pandemic, the meaning of “airborne disease” was not a point of confusion (let alone a politically charged issue). Airborne diseases were defined as being caused by aerosolized pathogens -- i.e., pathogens that are suspended in the air -- and are capable of infecting others at a significant distance. The air quality and long-range transmission implications of airborne diseases were well understood, years before the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Indeed, the need for airborne precautions for the control of SARS-CoV-1 was clear 20 years earlier. When COVID came along, the Director-General of the WHO first admitted (in February of 2020) that the disease was airborne, before bizarrely backtracking in the same press conference, stating that it was airborne “in the military sense” (If you can’t make sense of that statement, don’t worry. You’re not the only one).

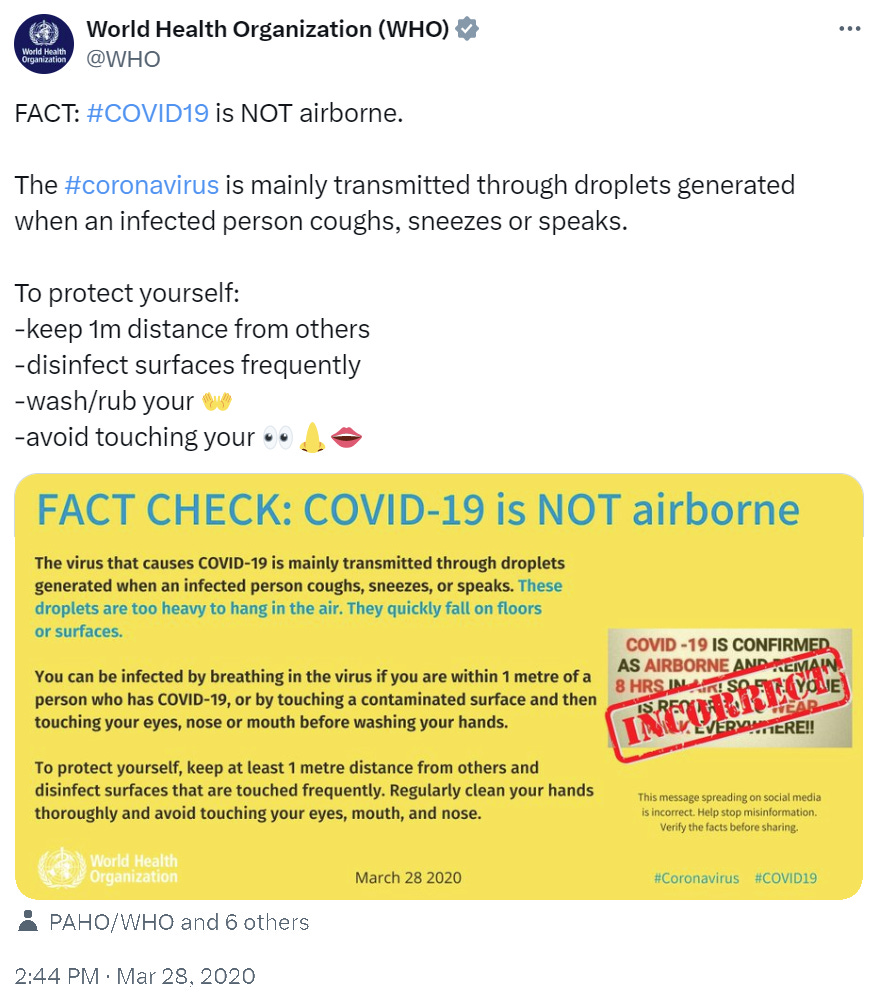

The WHO even went so far as to issue a “fact check” emphatically stating that COVID-19 was not airborne.

The “fact check” stating that COVID-19 is not airborne by the WHO from March 28, 2020. This tweet has never been deleted or corrected by the WHO.

The WHO’s position was met with substantial skepticism even at the time. Even as evidence piled up that SARS-CoV-2 transmission is indeed airborne, and clear guidelines were formulated to limit its spread, the WHO dug in. The infection control recommendations promoted by the WHO and other public health agencies focused on handwashing and the six-foot rule, both of which were clearly inadequate for an airborne disease – and, of course, this had major adverse consequences The confusion around aerosol transmission persisted, feeding off ill-conceived historical debates about the distinction between droplets and aerosols, and those who opposed a clear understanding of aerosol transmission did so by exploiting the linguistic confusion created. While there may be debate about what constitutes an aerosol and what constitutes a droplet, at the end of the day there should never have been debate about whether SARS-CoV-2 was airborne- that is, capable of transmitting at long ranges and thus requiring appropriate precautions.

It took two years for officials to deliver a reluctant acknowledgement of airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2, and even then the inadequate droplet-based guidelines remained largely unaltered. By then, enormous damage had already been done. Most recently, a group of 100 scientists working with the WHO produced a 50-page “Global technical consultation report on proposed terminology for pathogens that transmit through the air”, in which they noted that “during the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic, the terms ‘airborne’, ‘airborne transmission’ and ‘aerosol transmission’ were used in different ways by stakeholders in different scientific disciplines, which may have contributed to misleading information and confusion about how pathogens are transmitted in human populations.” Indeed, and – again – the WHO adamantly and repeatedly denied that SARS-CoV-2 was “airborne” under any of these definitions for years.

Rather than simplifying and clarifying the concept of “airborne” or “aerosol transmission”, the 2024 WHO report muddies the water (or rather, clouds the air) by adding more linguistic epicycles in the form of – quote -- ‘infectious respiratory particles’ or IRPs” which are “exhaled as a puff cloud”. The report acknowledges that the concepts of “waterborne” and “bloodborne” (see also “food-borne” and “vector-borne”) are widely accepted and well understood, but introduces the new term “transmission through the air”, which takes two forms: “airborne transmission/inhalation” (inhaled aerosols) and “direct deposition” of “semi-ballistic” particles (read: droplets). One could be forgiven for seeing this as an effort to retcon droplet transmission to count as “transmitted through the air” (in the military sense?) after having emphatically denied the airborne transmission in favour of droplet transmission for the first two years of the pandemic.

Not surprisingly, this redefining of terminology has been met with criticism by those who (correctly) advocated for airborne mitigations throughout the pandemic. As noted in a letter to The Lancet, “controlling words won’t control transmission”. As has happened multiple times during the pandemic, instead of changing course in the face of new (and, indeed, old) facts in a way that would have led to more effective mitigation, public health officials have instead added linguistic epicycles in order to maintain their commitment to a fundamentally flawed model of transmission.

Viral strains, variants, and subvariants

Another term that was redefined early in the pandemic was the term “viral strain”. Before this pandemic, we had a term for a virus “that is built differently, and so behaves differently, to its parent virus”, and that word was strain. In the early months of the pandemic, much ink was spilled about how evolution would not be a concern for SARS-CoV-2, that immune escape would not evolve, that vaccines and our immune systems could easily keep up with any changes in the virus, and so on. Then a new mutation (D614G) arose, and spread widely throughout the globe in a matter of months. We were assured that this was to be expected, but the change would not be functionally significant. Then it was shown to be functionally significant. There were, of course, very good reasons based on basic evolutionary theory to expect that a virus infecting billions of hosts would indeed evolve quickly and would evolve to evade human immunity (as was predicted by a team led by one of us (A.C.) in the winter of 2020).

The WHO responded by coining a new term, “viral variant” to mean a virus “that is built differently, and so behaves differently, to its parent virus”, seemingly ignoring the fact that a term already existed for the exact same concept. These variants were then assigned Greek letters for a few months, until the emergence of Omicron BA.1.

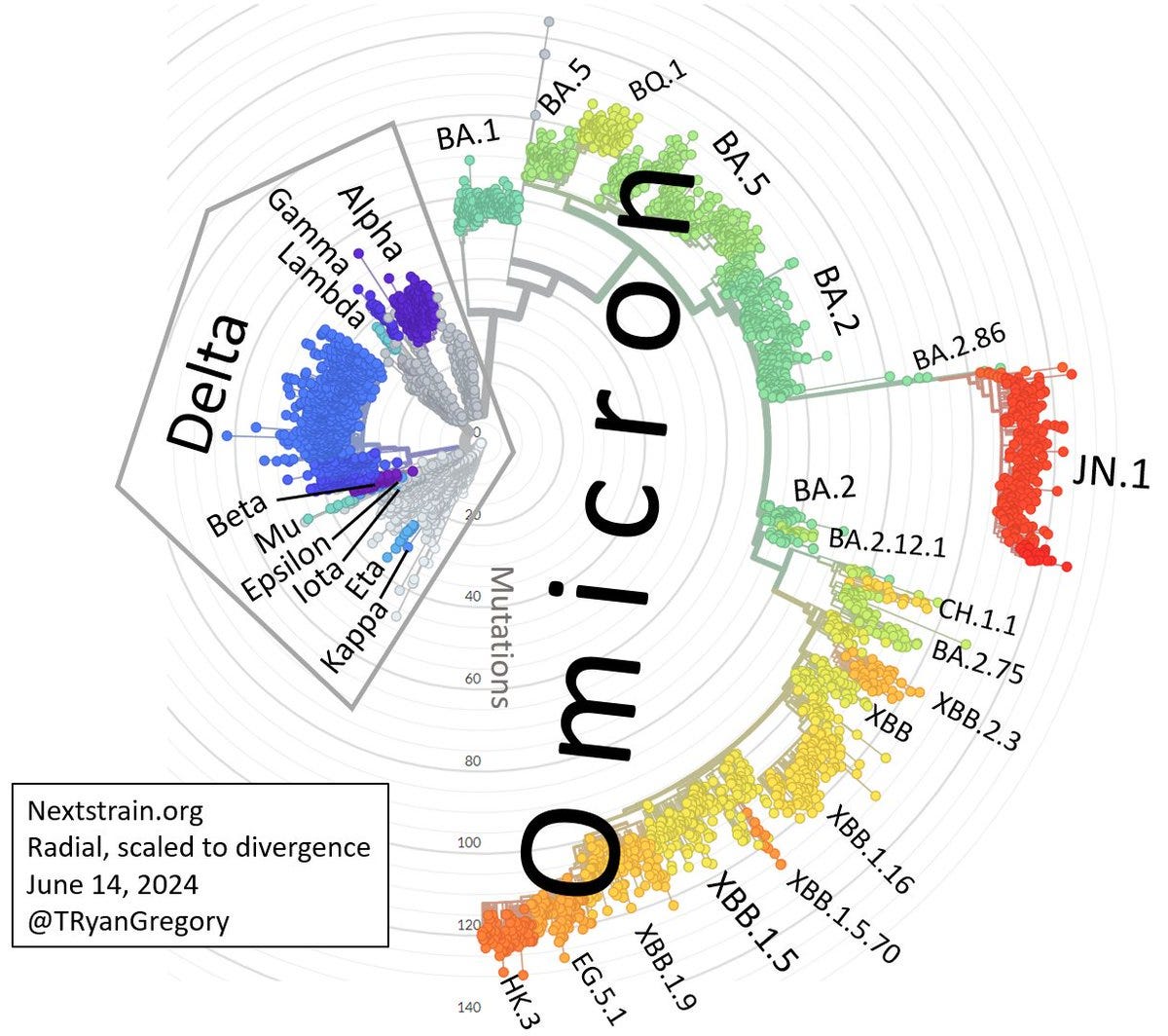

Evolutionary tree of SARS-CoV-2 variants from http://nextstrain.org, showing that “Omicron” subvariants are far, far more diverse and divergent from one another than the other variants that received new Greek letter nicknames in 2021.

With the dramatic adaptive radiation seen in the post-Omicron era, SARS-CoV-2 evolution has spawned large numbers of viruses that are both genetically and functionally different from their parent variant as well. In holding off on assigning Greek letters to these progeny, a de facto term, “sub-variant” now holds the space occupied by the previous incumbent, “variant”, which means a virus “that is built differently, and so behaves differently, to its parent virus”. So now we have three terms for the same concept. Here again, etymological imprecision has served to create confusion. In the public’s mind, it’s all still Omicron. Unlike other diseases, such as influenza, where we talk about pandemic and non-pandemic strains, with Covid, no such conversation is even possible, because it’s all Omicron, and Omicron is evolving, because “that’s just what viruses do”. Having three terms for the same concept has led to a less effective public health response, because public health has been focused on managing the public relations fallout of viral evolution rather than its public health implications.

The mechanism used to name variants itself has been subject to chaotic, epicycle-style revisions. The WHO designated 13 Greek letters for “variants of concern” (VOCs) and “variants of interest” (VOIs) over a period of ~180 days between May and November 2021. No new letters have been allocated since “Omicron”, despite there been >2,000 designated “subvariants”, several of which caused distinct waves of infections, hospitalizations, and deaths. The working definitions for VOCs and VOIs have been updated and VOIs are no longer given letters. “Omicron” as a VOC was retroactively said to refer only to the original variant B.1.1.529 and not any of those that caused major subsequent waves. According to these revised criteria, there are no current VOCs, and it is unlikely that anything descended from within the “Omicron” lineage would be considered to meet the threshold, despite the fact that some clearly have met the requirements. Notably, a need to update vaccines alone is listed as a sufficient reason for designation as a VOC and thus receiving a new Greek letter – something that has already happened twice in the “post-Omicron” era.

Variant-naming epicycles have made it possible to continue to claim that “it’s all Omicron” – which, by any reasonable biological standard, is clearly misleading. The communication vacuum left by the refusal to use the existing naming system for more than 2 years has since been filled by others who propose informal “common names” or “nicknames” for the most significant variants, but once again the damage done to public understanding and public health policy remains and continues to accrue.

Immunity

Few topics have undergone as many epicyclical revisions during the pandemic as those involving concepts of “immunity”. This has included bait-and-switch changes to the meanings of terms that have long been understood like individual-level “immunity” as protection from infection and “herd immunity” at the level of populations. It has also involved the coining of new terms to describe mundane phenomena that do not need new names while simultaneously prompting conflation with junk science ideas such as “hybrid immunity” and “immunity debt”.

When it came to the supposed pandemic-ending power of vaccines, we were sold a bill of goods by prominent public health officials and politicians. Vaccines were presented as providing robust protection against infection at the individual level and as ushering in much-coveted “herd immunity” at the population level once enough of us had received our shots. Remember the messaging around being “vaxxed and relaxed” and the “hot vax summer” that never materialized thanks to the Delta variant in 2021?

Once again, against the overly optimistic public health narrative there were many concerns being raised about whether herd immunity would be forthcoming with a virus like SARS-CoV-2. It was predictable (and predicted) as early as the winter of 2020 that vaccines alone would not bring the pandemic to an end, and it was predictable (and predicted) in the spring of 2021 that relaxing mitigation measures too early would lead to a variant-driven rebound.Public health ignored those concerns before the fact, focusing instead on reassurance.

After it became clear that vaccines did not prevent infection (let alone remove the risk of long COVID), the use of the term “immunity” at the individual level shifted from promising “not getting infected” or “not getting sick” to “still getting infected and quite possibly getting sick but not getting severely ill or dying”. Epicycles upon epicycles.

As it became evident that even widespread vaccination would not end transmission, some experts suggested that this was, in fact, “ok”, or that while we may not achieve herd immunity perhaps we can hope for a presumably less ambitious outcome of “herd resistance”. Soon, some authors were suggesting that anyone still waiting for herd immunity needed to “let go” and “move on”. While “herd immunity” through vaccination was abandoned as a pipe dream, it was soon replaced by the equally optimistic (and potentially ruinous) idea of “robust hybrid immunity” acquired through a combination of vaccination and infection. Some experts have gone so far as to advocate for the maintenance of this (partial, temporary, but somehow also “robust”) “hybrid immunity” through repeated infection.

In other words, adding epicycles has brought us full circle back to the dangerous idea of hoping for infection-based herd immunity, in the absence of mitigation efforts. This choice brings significant tail risk with it, including the emergence of serotypes (think a second SARS-CoV-2 pandemic running in parallel with the first), sudden failure of hybrid immunity due to immune evasion, and a growing burden of long-term and delayed health consequences of COVID-19 in the population.

“Immunity debt” is another epicyclic neologism added by infectious disease minimizers during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. This new term instantly generated more confusion than clarity by being used in reference to two very different ideas, one of which is trivially true at the population level (and does not need a new name) and the other of which is dangerous nonsense at the individual level. That is, “immunity debt” has been taken to mean that a widespread lack of exposure to common pathogens in one year will leave more people without immunity in a subsequent year when transmission resumes. Logically, this should result in a proportionate increase in cases in the following year as population level immunity catches up. It does not obviously predict that there will be surges of cases for years after a period of lower transmission, or an increase in severity. And yet, despite criticism of the misuse of the concept, “immunity debt” continues to be invoked as the explanation for all manner of unusual, atypically abundant, or unexpectedly severe outbreaks of any number of diseases in 2024 as a result of “lockdowns” in 2020. The obvious alternative hypothesis – that COVID infections increase susceptibility to other pathogens for some period of time (“immunity theft”), and/or that co-infection with COVID makes other infections worse – is rarely considered.

The individual-level version of “immunity debt” is even more dangerously misguided. Under this view, the immune system is “like a muscle” that “needs to be worked out” or it becomes atrophied and weak. The Orwellian implication is that infection with pathogens is actually good for the development of a strong immune system, and a lack of infection is detrimental to health. This is essentially a bastardization of the (still controversial) “hygiene hypothesis” which argues that exposure to commensal microbes is important for the normal development of a healthy immune system. To state the obvious, the hygiene hypothesis was never proposed for pathogenic microbes, and repeated exposure to disease cannot make you healthier.

Endemic

As with most of the others to which epicycles have been attached during the pandemic, “endemic” is a term that was generally well understood prior to 2020. Whereas an “epidemic” is a large, often sudden increase in the prevalence of a disease in a particular region and a “pandemic” is an epidemic scaled up across multiple regions, an “endemic” disease is one that persists at a relatively consistent and predictable level within a particular region. Being “endemic” says nothing about the amount of suffering and death wrought by a disease, and it certainly does not mean “harmless”. Malaria and tuberculosis – two of the deadliest diseases in the world – are both endemic in various regions, as are hepatitis, mpox, measles, chickenpox/shingles, and many others that are anything but benign.

When it became clear that herd immunity to SARS-CoV-2 was not forthcoming, and that any opportunity that may have existed to eradicate the disease through early mitigation had passed, the virus becoming endemic changed from being a failure to eradicate into a goal of public health – that is, “the path to endemicity” that would allow us to “learn to live with it”. One widely platformed infectious disease minimizer even titled her book about learning to live with SARS-CoV-2 “Endemic”. For other minimizers, endemicity has been seen as such a desirable outcome that children becoming infected as early as possible is described as a positive strategy. (Incidentally, this pro-infection philosophy is shared by proponents of the idea that the immune system is like a muscle, who believe that children being infected repeatedly is how COVID-19 will transform into a common cold).

Much of the desire for endemicity seems to be predicated on the hopeful- but false- expectation that viruses evolve to become milder over time, lest they drive their hosts and themselves to extinction. That is, by the time it becomes endemic it will be little more than an inconvenience – just another seasonal respiratory virus to which we will become accustomed. As has been pointed out repeatedly, there is no basis in either experience or evolutionary theory to support this notion and there are, in fact, reasons to expect that SARS-CoV-2 will not simply evolve toward benignity.

Getting off the merry-go-round

As with many other aspects of our disastrous pandemic response – from vaccine inequity, exhaustion and illness among the healthcare workforce, rejection of mitigation measures like respirators and cleaning indoor air, an emphasis on “you do you” individual health, and much else besides -- poor communication about SARS-CoV-2 has left us worse off for future pandemics. The focus on preventing “panic” (or avoiding accountability and deflecting demands for action, as the case may be) has led to a whole new vocabulary of misleading terms that all err in the direction of minimizing the risks of infectious disease.

The result has been a sort of etymological orrery, where meanings keep being updated as new facts arrived that should have been understood to challenge prevailing assumptions. The existence of these linguistic epicycles speaks to an underlying flaw in the epistemological model that has been used to form and communicate public health strategy over the course of the pandemic. The consistent use of language is key to building trust- redefining terms such as “strain”, “endemic” and “immunity” has not changed the reality. COVID-19 remains a serious disease with significant long-term consequences, the pandemic is nowhere near over, and significant tail risk exists in a strategy that permits rampant unmitigated spread of SARS-CoV-2.

Public health has spent much of its energy on public relations, normalizing repeated infection rather than doing its job, which is (checks notes) Disease Control. We do not need more epicycles that lessen fear about pandemic diseases, we need a new paradigm that properly emphasizes prevention. Otherwise, we can expect to go round and round as new and potentially even more dire pandemic threats continue to emerge.